HIT

Counter

Autoplay. Duration: 20 min.

Please view on a laptop or desktop computer with camera functionality enabled for interaction with artwork.

HIT

Counter

We sometimes get asked by business owners, “Why do I need a Visitor Counter?” Well, the answer is simple, it allows you to measure how effectively your business is running.

VOODOO

ECONOMICS

( or, MEASURING SUCCESS )

For art institutions, the success of art has historically been measured through the use of visitor numbers as a standard metric despite being largely unverifiable from a scientific point of view. Referred to as ‘voodoo economics’ by the late contemporary art curator Okwui Enwezor, the metric’s functionality relies on the accuracy of the counting methods used and the honesty of the galleries and museums to report without fudging their numbers to appear more successful.

By mapping attendance figures over time, art institutions can determine: the total number of visitors over an exhibition, event or other duration; which times of the day, week, or year are busy or quiet; how visitors travel through and use various spaces; which artworks, exhibitions, or parts of exhibitions are popular; how successful an advertising campaign, cross-promotion, or partnership has been in increasing visitor numbers; and whether visitors to the galleries are using peripheral spaces such as the shop, reading room, café, restaurant, or bar.

Extrapolating this data further can help to: suggest which elements of past exhibitions and events have contributed to well-attended outcomes; to predict the future traffic of exhibition periods based on patterns such as the season, holidays, annual programming events, and involvement in cultural programs such as festivals; to establish and measure the achievement of KPIs; to apply for, and to justify, funding; and to compare the performance of institutions against one another.

Installing a people or visitor counter in your business enables you to measure how effective the effectiveness of your advertising where you can easily determine your sales conversion ratio – that is, comparing customers to transactions. This will help you work out if you need to staff your business more efficiently by knowing your customers-to-salesperson ratios throughout the day. It is when you consider how your staffing levels compare to the number of sales each hour, you can look at taking your business to the next level.

QUANTITY

VERSUS

QUALITY

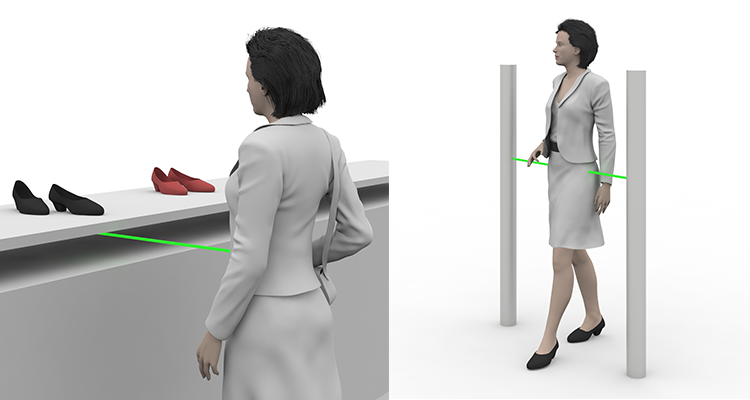

Outside of ticketed experiences, which can be tracked through ticket sales, visitor numbers for art and culture are often counted manually using handheld tally counters; or through methods using pressure-sensitive mats, or infrared break-beams positioned across doorways. Increasingly, however, these metrics are being produced using technology developed for more commercial applications relying on thermal or video camera sensors, Wi-Fi trackers and Bluetooth beacons, or video counters using advanced machine learning algorithms.

Although each method has its advantages and disadvantages in terms of affordability, accuracy, privacy, installation and environmental requirements, these methods can only record the number of people in attendance and not the quality of the experience had by those in attendance. Despite efforts to implement visitor feedback systems such as the use of surveys and the monitoring of press and reviews to better gauge visitor experience in a qualitative sense, the measure of success for art and culture remains mostly quantitative.

In a debacle at London’s National Portrait Gallery in 2018, it was discovered that an error caused by a third-party visitor counting system had wrongly been recording a 50% decrease in attendance figures over a substantial 2017–18 period when it was, in fact, only a 10% decrease. The error caused: concerns raised by the government over their funding of the NPG; damage to the gallery’s reputation at a time when national visitor numbers were already dwindling; difficulties soliciting sponsorship and donations amidst negative press; and criticism from the media that the steep decline was a result of programming aimed at an art world audience at the expense of accessibility to the general public.

We’ve put together some of the benefits of visitor counting:

- You can automate your counting system with state-of-the-art technology

- Compare performance data of multiple locations in business

- Quantify changes to store layout and in-store promotions

- Automate attendance for community events, churches, and more

- Maintain employee integrity through automation

[ … ]

[ … ]

- Evaluate sales conversion ratios (traffic-to-sales)

- Comply with safety regulations and fire codes

- Measure results of marketing campaigns

- Produce efficient staffing schedules

- Justify government funding

Essentially, your business can only benefit from the use of a visitor counter, ultimately with increased sales and increased profit.

Attention

SCARCITY

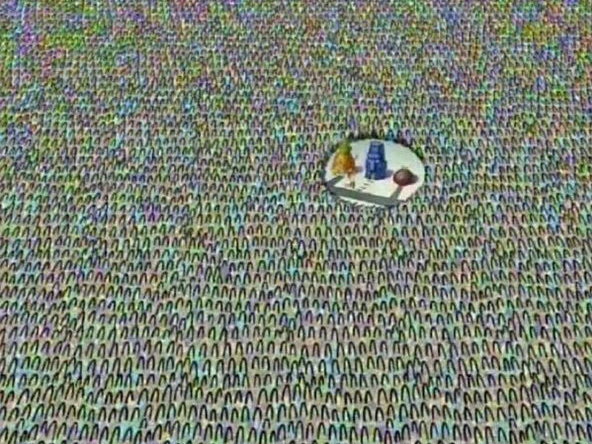

Throughout the 2010s, the long-standing relationship that once existed between producers and spectators of art and culture became inverted as a result of globalisation, the ever-expanding internet, smartphones, and the omnipresence of social media. Where a small selection of celebrated individuals would produce art and culture for a vast number of spectators previously, it is now the case that a vast number of individuals produce art and culture for smaller audiences with less time and attention.

From a study conducted in 2001 at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and a study conducted in 2016 at The Art Institute of Chicago, it was found that the average amount of time visitors spent looking at ‘great’ works of art had not changed much with an increase from 27.2s to 28.63s. Interestingly, it was how the visitors spent that time that had changed with a large percentage of visitors, regardless of gender, apparent age, or group size, taking ‘arties’ (i.e. art selfies) with each artwork: in effect, turning an act of spectatorship into an act of production.

With more opportunities than ever before available for individuals to produce, consume, and become fatigued by content; and with less filtering and quality-control occurring between content and audiences; art institutions must now work significantly harder to compete for attention and maintain audiences. In today’s attention economy, it is human attention that is the scarcest commodity.

ACCESS

to

TOOLS

In the late 1990s, early web developers helped to progress web analytics with the invention of the ‘hit counter’ or web counter: a PHP script showing an image of a number that increased each time the script ran, or the webpage refreshed. Often resembling an odometer but available in many styles, the code for hit counters could easily be copied-and-pasted, which led to their popularity on webpages hosted on sites like Geocities and Angelfire before appearing on early social media platform MySpace.

Before the hit counter was invented, it was only through the expensive and time-consuming analysis of website server logs that website analytics existed. Even then, the process was primarily used for debugging and preventing server failure instead of recording visitor statistics. Today, analytics tools varying in complexity are built into all online social platforms with everyone from individuals to influencers and celebrities to businesses using them to keep track of their audience engagement, no matter how big or small.

In addition to tracking metrics across their physical spaces, galleries and museums must now also manage multiple accounts across different online platforms, create platform-specific content, and track metrics across websites, social media platforms, online shops, email, and advertising campaigns in order to keep up with new technology and to maintain visibility in a highly competitive attention economy.

GOING

PUBLIC

Throughout Western history, the focus of galleries and museums has often shifted between being spaces both of and for the general public and being spaces dedicated to the disembodied contemplation of art.

Frederick Mackenzie, The National Gallery when at Mr J. J. Angerstein's House, Pall Mall, c.1824–34

From the 17th century onwards, privately established museums began to open to the general public with royal collections becoming nationalised and private art collections being made increasingly accessible to the public. By the 19th century, the new public museum, much like the often surrounding or adjoining new public park, had become as much an escape from the hustle and bustle of the metropolis (or a substitute for the park in bad weather) as it was a place to contemplate art and culture.

Giuseppe Gabrielli, Room 32 in the National Gallery, London, 1886

Towards the end of the 19th century, the museum took on the task of educating an emerging middle-class art audience, and began to frown upon and even explicitly forbid previously acceptable activities such as playing, eating, drinking, talking, laughing, and napping within the galleries. This changing attitude is evident in an 1850 report in which the keeper of London’s National Gallery complained of visitors, often “country people”, rearranging furniture, making themselves comfortable, and feasting on significant spreads in the middle of the galleries.

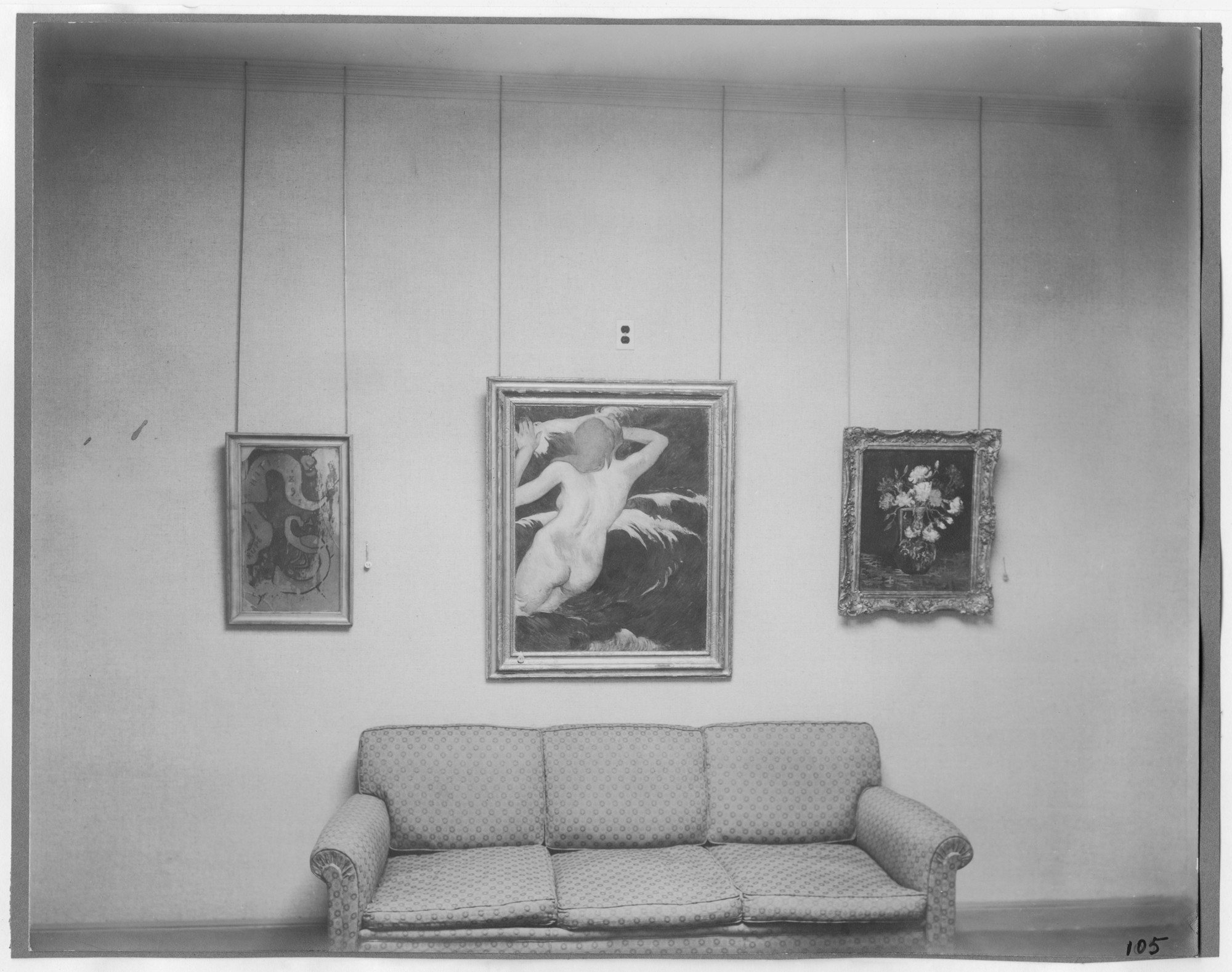

Installation view of the exhibition Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh, MoMA, 7 November – 7 December, 1929

Inside the

WHITE

CUBE

In a historical account of the gallery bench by architect Joel Sanders and professor of literature, film and feminist studies Diana Fuss, the growing uncertainty of the museum’s priorities can be seen in the replacement of individual moveable chairs with the gallery bench, benches similar in form and function to those of the public parks and the private gardens of palaces prior. Along with the introduction of stanchions to protect artworks from the general public, the placement of exhibition furniture became a way to help control traffic.

Providing both a platform for viewing art and other visitors and a place to rest, the gallery bench and its users were seen as a distraction from the contemplation of art by the modern art museum. With the increasing adoption of the ‘white cube’ style, which borrowed heavily from department store aesthetics, the seating within galleries became limited, removed altogether, or used only in liminal spaces. With a function similar to that of the church pew with the intent of focusing attention, the gallery bench became more uncomfortable with the removal of all armrests and back supports to discourage lounging, napping, or sitting for long periods.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Barcelona Couch, 1930

Designed to eliminate awareness of the outside world, the new ‘white cube’ typically favoured sealed windows to eliminate distractions, artificial light over natural, removal of any architectural details that might detract attention from artworks, and either polished wooden or concrete floors. On the opening of New York’s MoMA in 1939, art critic Henry McBride said of this new style: “Apparently, in the new museum, we shall be expected to stand up, look quickly and pass on. There are some chairs and settees, but the machine-like neatness of the rooms does not invite repose.”

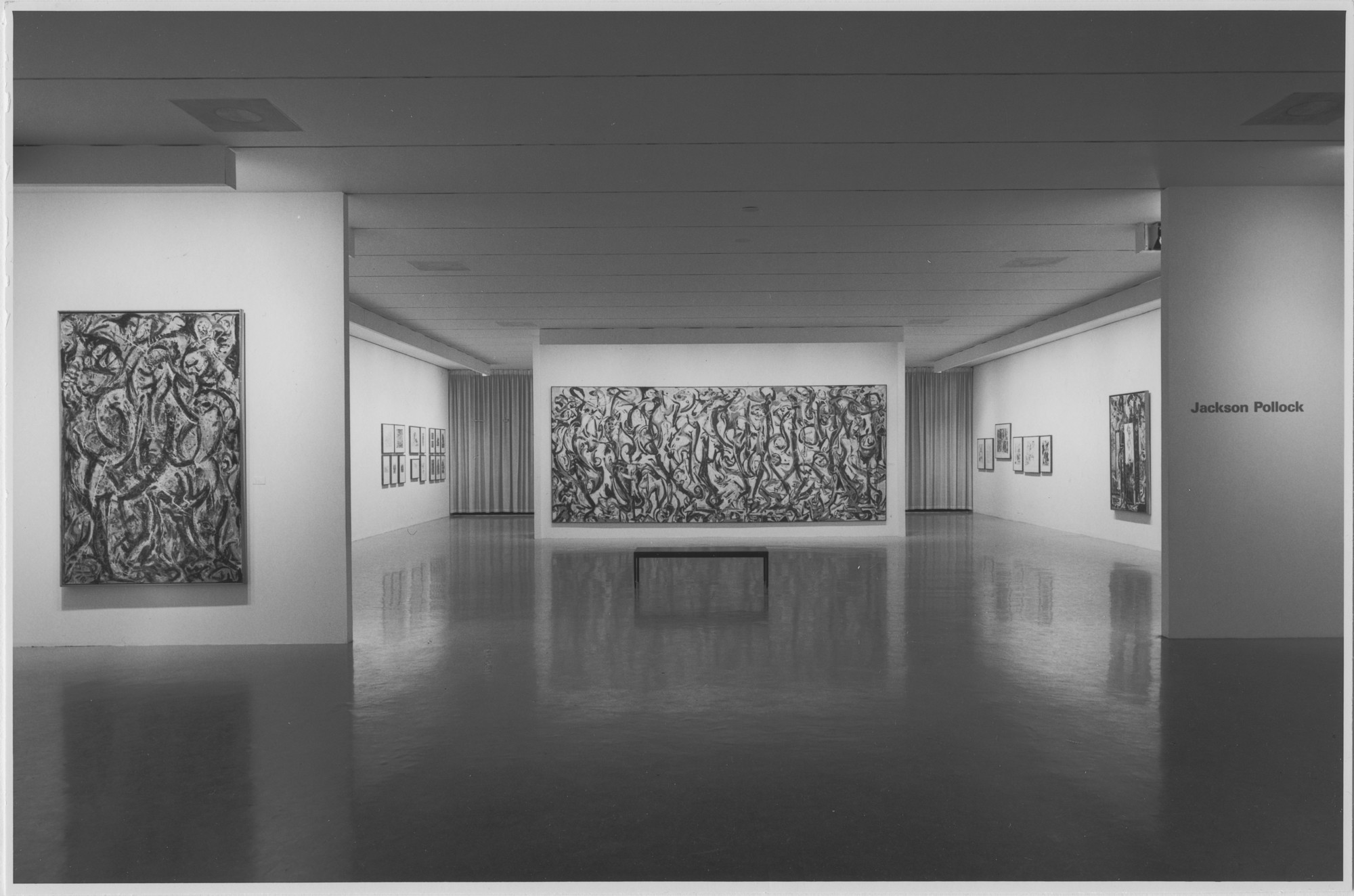

Installation view of the exhibition Jackson Pollock, MoMA, 5 April – 4 June, 1967

The real-time counts for each area means that the museum can allocate extra staff or security guards to popular exhibits. Items are more often damaged or stolen in busy rooms with few personnel on duty.

Many museums are funded by governments, and receive their funding according to how many visitors they get. Video people counting gives a true number of visitors, rather than basing the footfall figure on the number of tickets allocated (for example when a bus-load of children get in under one group ticket), thus helping grant applications.

[ … ]

[ … ]

The information collected also enables museums to adapt floor layouts to increase visitor satisfaction and encourage repeat visits.

The data is not just useful for enhancing the visitor experience, the system will also increase sales in the museum shop.